Medical

HIV Preventive Care Is Supposed to Be Free in the US. So, Why Are Some Patients Still Paying?

The Department of Labor issued rules in July clarifying that health plans need to cover the costs of prescription drugs proven to prevent HIV infection, along with related lab tests and medical appointments, at no cost to patients. More than half a year later, the erroneous billing continues.

This article originally appeared in Kaiser Health News.

Anthony Cantu, 31, counsels patients at a San Antonio health clinic about a daily pill shown to prevent HIV infection. Last summer, he started taking the medication himself, an approach called preexposure prophylaxis, better known as PrEP. The regimen requires laboratory tests every three months to ensure the powerful drug does not harm his kidneys and that he remains HIV-free.

But after his insurance company, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas, billed him hundreds of dollars for his PrEP lab test and a related doctor’s visit, Cantu panicked, fearing an avalanche of bills every few months for years to come.

“I work in social services. I’m not rich. I told my doctor I can’t continue with PrEP,” said Cantu, who is gay. “It’s terrifying getting bills that high.”

A national panel of health experts concluded in June 2019 that HIV prevention drugs, shown to lower the risk of infection from sex by more than 90%, are a critical weapon in quelling the AIDS epidemic. Under provisions of the Affordable Care Act, the decision to rate PrEP as an effective preventive service triggered rules requiring health insurers to cover the costs. Insurers were given until January 2021 to adhere to the ruling.

Faced with pushback from the insurance industry, the Department of Labor clarified the rules in July 2021: Medical care associated with a PrEP prescription, including doctor appointments and lab tests, should be covered at no cost to patients.

More than half a year later, that federal prod hasn’t done the trick.

In California, Washington, Texas, Ohio, Georgia, and Florida, HIV advocates and clinic workers say patients are confounded by formularies that obfuscate drug costs and by erroneous bills for ancillary medical services. The costs can be daunting: a monthly supply of PrEP runs $60 for a generic and up to $2,000 for brand-name drugs like Truvada and Descovy. That doesn’t include quarterly lab tests and doctor visits, which can total $15,000 a year.

“Insurers are quite smart, and they have a lot of staff,” said Carl Schmid, executive director of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute. They are setting up “formularies in a way that looks like I’m going to have to pay, and that’s one of the barriers. They are not showing this is free for people in an easy way.”

Schmid has found repeated violations: bewildering drug formularies that wrongly assign copays; PrEP drugs listed in the wrong tier. Some plans offer zero-cost access only to Descovy, a patented drug Gilead Sciences tested only in men and transgender women that is not authorized by the FDA for use by women who have vaginal sex.

More than 700,000 Americans have died from HIV-related illnesses since the AIDS epidemic emerged in 1981. But compared with its devastating impacts in the 1980s and ’90s, HIV is now largely a chronic disease in the U.S., managed with antiretroviral therapy that can suppress the virus to undetectable — and non-transmissible — levels. Public health officials now promote routine testing, condom use, and preexposure prophylaxis to prevent infections.

“Contracting HIV or AIDS is not a fear of mine,” said Dan Waits, a 30-year-old gay man who lives in San Francisco. “I take PrEP as an afterthought. That’s a huge shift from a generation ago.”

Still, 35,000 new infections occur each year in the U.S., according to KFF. Of those, 66% occur through sex between men; 23% through heterosexual sex; and 11% involve injecting illegal drugs. Black people represent nearly 40% of the 1.2 million U.S. residents living with HIV.

HIV prevention drugs, including a long-lasting injectable approved by the FDA last December, are critical to reducing the rate of new infections among high-risk groups. But uptake has been sluggish. An estimated 1.2 million Americans at risk of HIV infection should be taking the pills, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, but only 25% are doing so, and use among Black and Hispanic patients is especially low.

“Until we can increase uptake of PrEP in these communities, we’re not going to be successful in bringing about an end to the HIV epidemic,” said Justin Smith, director of the Campaign to End AIDS at Positive Impact Health Centers in Atlanta. Among U.S. metropolitan areas, Atlanta has the second-highest rate of new HIV infections, after Miami.

Women remain a neglected group when it comes to PrEP education and treatment. In some urban areas, such as Baltimore, women account for 30% of people living with HIV. But women have been largely ignored by PrEP marketing efforts, said Dr. Rachel Scott, scientific director of women’s health research at the MedStar Health Research Institute in Washington, D.C.

Scott runs a reproductive health clinic that cares for women with HIV and those at risk of infection. She counsels women whose sexual partners do not use condoms or whose partners have HIV and women who have transactional sex or share needles to consider the HIV prevention pill. Most, she said, are completely unaware a pill could help protect them.

In the years since Truvada, the first HIV prevention pill authorized by the FDA, was approved in 2012, lower-priced generic versions have entered the market. While a monthly supply of Truvada can cost $1,800, generic prescriptions are available for $30 to $60 a month.

Even as medication costs have decreased, lab tests and other accompanying services are still being billed, advocates say. Many patients are unaware they do not have to pay out-of-pocket. Adam Roberts, a technology project manager in San Francisco, said his company’s health insurer, Aetna, has charged him $1,200 a year for the past three years for his quarterly lab tests.

“I assumed that was the cost of being on the medication,” said Roberts, who learned about the issue from a friend in January.

Enforcing coverage rules falls to state insurance commissioners and the Department of Labor, which oversees most employer-based health plans. But enforcement is driven largely by patient complaints, said Amy Killelea, an Arlington, Virginia-based lawyer who specializes in HIV policy and coverage.

“It’s the employer-based plans that are problematic right now,” said Killelea, who works with clients to appeal charges with insurers and file complaints with state insurance commissioners. “The current system is not working. There need to be actual penalties for noncompliance.”

A spokesperson for the Department of Labor, Victoria Godinez, said that people who have concerns about their plan’s compliance with the requirements should contact the Department of Labor’s Employee Benefits Security Administration.

Even as they push for broader enforcement, HIV organizations are taking one small victory at a time.

On Feb. 16, Anthony Cantu received a letter from the Texas Department of Insurance informing him that Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Texas had reprocessed his claims for PrEP-related lab costs. The insurance company assured state officials that future claims submitted through Cantu’s plan “will be reviewed to make sure the Affordable Care Act preventive services would not be subject to coinsurance, deductible, copayments, or dollar maximums.”

The news was welcome, said Schmid of the HIV+Hepatitis Policy Institute, but “it shouldn’t have to be so hard.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Medical

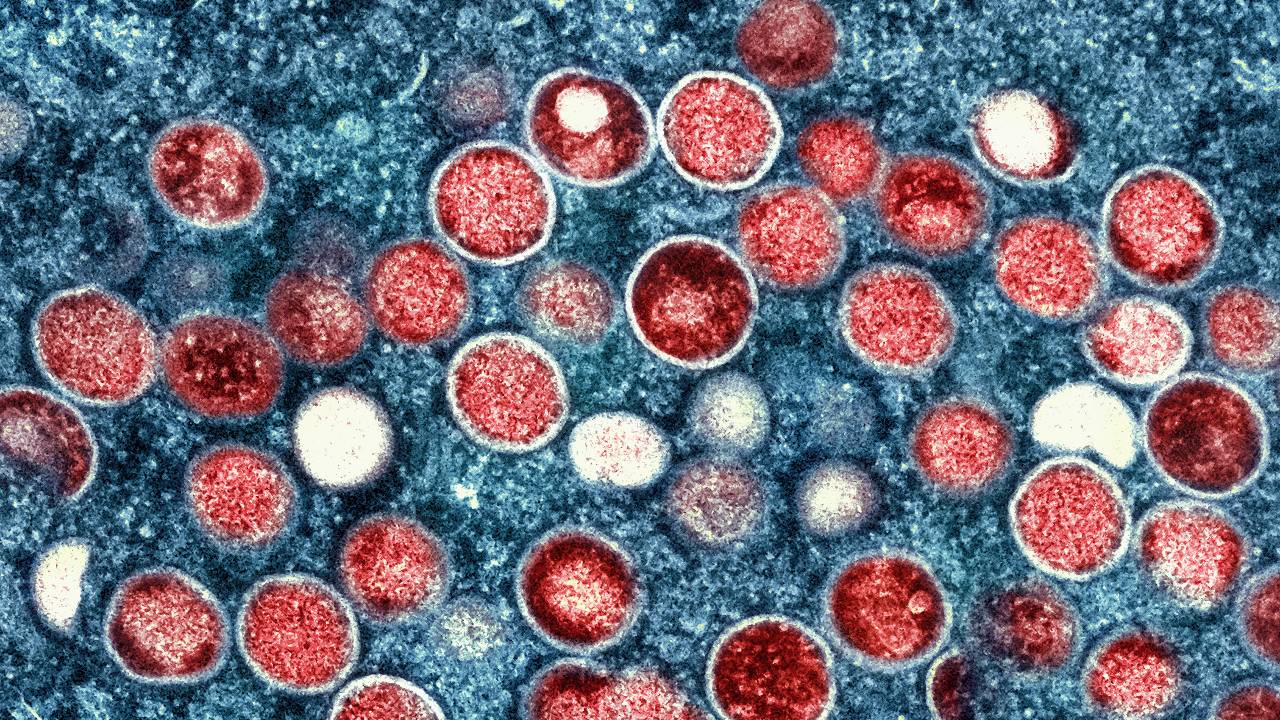

Experts debunk monkeypox myths as misinformation spreads

Can monkeypox spread on the subway? Can it kill like COVID-19? Experts respond to monkeypox myths and misconceptions.

This story was originally published by The 19th

Can monkeypox spread on the subway? Can it kill like COVID-19? Is it transmitted through sex?

Can monkeypox spread on the subway? Can it kill like COVID-19? Is it transmitted through sex?

Misconceptions, myths and a lack of public knowledge on the monkeypox virus are widespread. Despite 57 percent of adults recently polled by Morning Consult feeling confident in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ability to control the spread of monkeypox, many Americans are misinformed on how the virus spreads and how concerned they should be right now — as they face the virus for the first time.

Last month, the Annenberg Public Policy Center found that nearly half of 1,580 surveyed adults were not sure if monkeypox was less contagious than COVID-19. (It is much less contagious.) One-third of more than 4,000 adults polled by Morning Consult aren’t sure how monkeypox spreads. Two-thirds of those surveyed by Annenberg were unsure or didn’t believe that there is a monkeypox vaccine (there is, it’s FDA-approved, and to be eligible for a vaccine right now in most areas, people must be in a high-risk group — predominately queer men, or trans and nonbinary people, who have had multiple or anonymous sex partners in the last two weeks.).

Monkeypox is a disease primarily transmitted through skin-to-skin contact that can infect anyone, but is currently affecting queer men the most.

Here’s what experts have to say in response to common misconceptions and myths about the monkeypox virus.

People can get monkeypox on public transit, in dressing rooms, or while shopping: False

The risk of getting infected through these situations is extremely low, said Stephen Abbott, medical director at Whitman-Walker’s Max Robinson Center, a D.C.-based healthcare provider focused on serving LGBTQ+ people.

Abbott stressed that spread occurs through direct skin-to-skin transmission — not skin-to-object, then someone else touching that object. The virus can spread by touching sex toys, sheets and other fabrics that have made contact with exposed lesions or skin rashes, per the CDC — but the vast majority of cases are being reported by men who had sex or close intimate contact with another man prior to infection.

Places where a person could typically pick up a cold or flu virus are not considered primary points of transmission.

“There’s really no evidence at this time to suggest people are being infected through casual contact through public transportation, and anything like that. The vast majority of the cases that have been identified from the outbreak so far had been through intimate contact or sexual activity,” said Daniel Uslan, co-chief infection prevention officer at UCLA Health and clinical chief of infectious diseases.

Monkeypox can spread through shaking hands or hugging: Not likely

These are also very low-risk situations, Uslan said, adding that he is not aware of recorded cases where handshaking is the suspected route of transmission.

But skin-to-skin contact with someone who has an open lesion can still occur if those lesions are on the hands, Abbott noted — and some lesions are so small that patients don’t notice them.

“Some of the patients I’ve seen when I do their skin exam, they haven’t even noticed that they have a lesion on their hand,” he said. “They might inadvertently shake someone’s hand and expose them unknowingly.”

However, some of the fears surrounding the spread of monkeypox — especially from low-risk encounters in public spaces — seem to manifest from anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment, as gay and bisexual men are primarily contracting the virus right now, said Perry Halkitis, dean and professor of public health and health equity at Rutgers School of Public Health.

“People will use any piece of information, if they are homophobic, to disadvantage and to stigmatize gay men,” he said.

Monkeypox is an STD or STI: False, but sexual contact is still driving the spread.

The virus can spread through any prolonged skin-to-skin contact with lesions or rash areas — but transmission during sex, where plenty of skin-to-skin contact takes place, is still primarily how the virus is spreading right now.

“You can have sex with somebody and have the flu, and they can get the flu. That doesn’t make the flu an STI,” Halkitis said. Oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse are not required for monkeypox transmission to occur, he added.

“Technically, it is not [an STD or STI] because it is not solely spread through sexual contact. But the current outbreak appears to be spreading primarily through sexual contact, so it is associated with sex, but is not technically a sexually transmitted infection,” Uslan said.

Abbott agreed that, by definition, monkeypox is not an STI or STD. Josh Michaud, associate director of global health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, noted that the answer should ultimately not affect how the country responds to the virus — and that labeling the virus as an STI may not be black or white.

“What we know is that sexual behavior, or particularly men who have sex with men with multiple partners, has been the bulk of the cases so far of monkeypox. And therefore transmission is very much associated with sexual activity,” Michaud said. “I think people are sort of debating terminology here. And we don’t necessarily need to classify it to be able to respond to it one way or the other.”

Having chickenpox or shingles protects someone from monkeypox: False

The virus that causes chickenpox is unrelated to monkeypox, although their names are similar.

“The viruses are in completely different families,” said Michaud. “In the case of the chickenpox virus, it doesn’t provide any cross-protection against monkeypox.”

Getting the smallpox vaccine as a kid protects against monkeypox: Likely

Someone who got the smallpox vaccine as a kid would likely have some protection against current monkeypox transmission, experts say, since the viruses are in the same family. However, any immunity provided by a childhood smallpox shot may have waned.

“Health departments are still suggesting that those folks get vaccinated,” Abbott said, adding that immunity may have waned because smallpox was declared eradicated in 1980.

The passage of several decades since smallpox vaccinations were commonplace means that most young people have not received the same level of protection, Uslan noted.

Monkeypox is as contagious, or as dangerous, as COVID-19: False

Monkeypox is not as contagious, or as fatal, as COVID-19, which is highly transmissible through airborne and respiratory routes.

“It is absolutely not as contagious as COVID,” Uslan said. Monkeypox is not spreading through casual contact, and evidence so far shows that patients are not contagious with monkeypox until symptoms emerge — as opposed to COVID-19, which asymptomatic people can spread.

“It’s also not nearly as fatal,” Abbott said, and it won’t leave you with a chronic infection. “It’s a rash that is very uncomfortable and painful. But most people will recover in two to four weeks.”

While scarring can be one long-term side effect, after the lesions heal, there haven’t been reports of a “long” monkeypox syndrome similar to the long COVID that many Americans have experienced.

People are at higher risk of contracting monkeypox if they’ve had COVID-19 before: False

There is no evidence to suggest that getting COVID-19 increases a person’s risk to contract monkeypox. While those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to contract a variety of viruses, Halkitis noted, contracting COVID does not mean someone is more likely to get monkeypox.

“With two different diseases, one doesn’t create exposure to the other,” Abbott said.

Children are at risk of getting monkeypox right now: False

Children are still at minimal risk. While the virus could spread into their social networks at some point, the current focus to slow the spread of the virus is to vaccinate men who have sex with men.

“I don’t think parents should be terribly worried at this time, but this is something that people should be paying attention to,” Uslan said. “We have not seen a lot of cases in daycare settings for children at this point. So it doesn’t seem to be a major concern.”

While a few monkeypox cases have been seen in women and children, and the potential for greater spread cannot be ignored, the difference in risk right now is still massive, Michaud said.

Everyone is at the same risk of getting infected right now: False

A person’s risk of getting infected with monkeypox is high right now if they are among high-risk groups like queer men who have recently had multiple sexual partners or anonymous sex, or aren’t using protection.

“If we’re gonna get ahead of this and keep it from escalating, we need to be vaccinating those at highest risk — gay and bisexual men and our networks, and trans folks as well,” Abbott said, noting that social networks within these groups can be vectors for spread alongside sexual networks.

“The highest-risk individuals in my view are young gay and bisexual men, born after 1972, who have no smallpox vaccination, and who are socializing in large groups with other gay men,” Halkitis said.

It’s not safe for people with eczema to get the JYNNEOS vaccine shot: False

It’s safe to get the JYNNEOS shot even with eczema or similar skin conditions. However, ACAM2000, an FDA-licensed smallpox vaccine that may also be effective against monkeypox but is not being widely offered due to a long list of side effects and a more difficult injection procedure, can be harmful to those with eczema and those with other exfoliative skin conditions or dermatitis.

TPOXX treatment is not safe for people living with HIV: False

TPOXX, the antiviral and primary pain management treatment for monkeypox,is safe for those living with HIV, including those taking antiviral drugs to manage their HIV, experts said. There are also no interactions between the JYNNEOS vaccine and HIV medications, Halkitis said.

More studies on TPOXX’s effectiveness are gearing up and are likely to start in the next few weeks, Uslan said, although it is already known that the treatment is safe and well-tolerated in healthy patients.

According to an analysis by the CDC of monkeypox cases from May through July, a substantial number of monkeypox cases have been reported among those with HIV.

Find more information on monkeypox symptoms, how the virus spreads, and what to do if you are sick from the CDC’s website.

Disclosure: Pfizer, CVS Health, the Human Rights Campaign, and the chairman of Enterprise Product Partners, Randa Duncan Williams, have been financial supporters of The 19th.

The 19th is an independent, nonprofit newsroom reporting at the intersection of gender, politics and policy.

Medical

FDA: Stop Using Poppers

FDA reports increased deaths, hospitalizations linked to the sexual stimulant ‘poppers’

The Food and Drug Administration has issued a warning advising consumers not to purchase or use nitrite “poppers” after an observed increase in reports of deaths and hospitalizations with issues such as severe headaches, dizziness, increase in body temperature, difficulty breathing, extreme drops in blood pressure, blood oxygen issues (methemoglobinemia) and brain death after ingestion or inhalation of nitrite “poppers.”

“‘Poppers,’ which are sold online or at adult novelty stores, may be marketed as nail polish removers but are being ingested or inhaled for recreational use or to enhance sexual experiences. These products contain nitrites, which are chemical substances that should not be ingested or inhaled unless specified/prescribed by a healthcare provider.”

“Brand names include Jungle Juice, Extreme Formula, HardWare, Quick Silver, Super RUSH, Super RUSH Nail Polish Remover and Premium Ironhorse, among others.”

While poppers were banned in Canada in 2013 and nearly banned in the U.K. in 2016, they remain legal in the U.S. The FDA says it will continue tracking reports of adverse events resulting from the ingestion or inhalation of nitrite “poppers” and will take appropriate actions to protect the public health. The agency also has contacted its federal partners alerting them of the recent adverse event reports.

Consumers who have experienced an adverse event (illness or injury) after using nitrite “poppers” should consult their healthcare providers. Consumers should also report their adverse events to MedWatch: FDA’s Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program and information about the products they used to Reporting Unlawful Sales of Medical Products on the Internet | FDA.

Recommendations for Consumers

- Do not purchase or use nitrite “poppers” for recreational use or sexual enhancement.

- Be aware of the serious risks, including death, associated with the use of these products and stop using them immediately. Discard any unused product.

- Contact your healthcare providers immediately if you are experiencing illness after using these products.

- Contact your healthcare providers if you have recently used these products and are concerned about your health.

Medical

One-third of gay and bisexual PrEP users discontinue use within three years

Familiarity and favorable attitudes towards PrEP have increased over time, though use remains low

A new study from the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law finds a significant increase in familiarity with pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among gay and bisexual men. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) regards PrEP as a highly effective tool to prevent the transmission of HIV. However, one-third (33%) of gay and bisexual men who were taking PrEP discontinued use over a three-year period.

Using data from the Generations Study, a national probability sample of LGB people in the U.S., researchers explored familiarity, attitudes, uptake, and discontinuation of PrEP among gay and bisexual men from 2016 to 2018. This is the first study to document longitudinal trends in PrEP use in a national probability sample of gay and bisexual men at risk for HIV.

Researchers found that among gay and bisexual men, attitudes toward PrEP were mostly positive, but more than a quarter (27%) of gay and bisexual men who were both eligible for and familiar with PrEP had a negative attitude towards it. While uptake of PrEP increased over the study period, overall use remained persistently low.

“Stigma around the use of PrEP, as well as concerns regarding long-term side effects and conflicting messages from AIDS service providers, may foster confusion around the benefits of taking PrEP,” said study author llan H. Meyer, Ph.D., Distinguished Senior Scholar of Public Policy at the Williams Institute. “Multi-level interventions are needed to improve education, reduce barriers to access, and promote use among gay and bisexual men.”

Key Findings

- PrEP familiarity increased considerably between 2016 and 2018 among those eligible for PrEP from 60% to 92%.

- Favorable attitudes toward PrEP increased more modestly from 68% in 2016 to 73% in 2018.

- PrEP use increased by 90% between 2016 (4%) and 2018 (8%). However, overall use among eligible men remained low.

- Among respondents who reported PrEP use, 33% subsequently discontinued PrEP.

“PrEP uptake has been slow, especially among racial/ethnic minority gay and bisexual men,” said lead author Ian W. Holloway, Associate Professor of Social Welfare at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs. “We’re hopeful that new innovations in PrEP delivery, including on-demand dosing and injectable PrEP, can help expand PrEP coverage with diverse gay and bisexual men in the coming years.”